Trip Report (Historical) - South Africa to the UK, September 1998 - Part 2

Day Two - Windhoek to Libreville

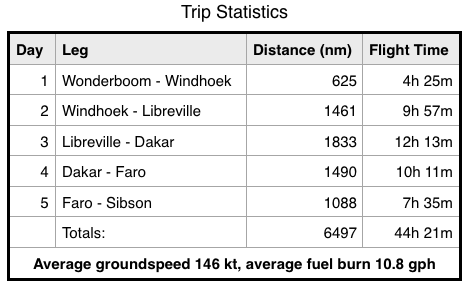

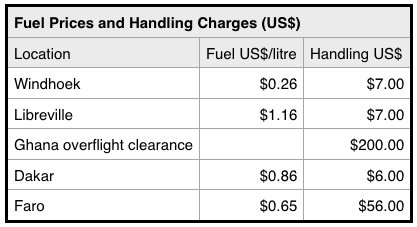

We were back at Windhoek International at a comfortable 7:30 local with an hour to go to our planned departure time. I filed the flight plan, paid the landing fee and checked the weather (severe clear as far as the local met-man could tell), while Steve pre-flighted the Bonanza and then set off on an expedition to refill our coffee flask. This he achieved by walking up the steps of a parked Air Namibia Airbus and scrounging the coffee from the inflight galley. I was then able to blame him for the ten-minute delay in our departure, but at least we had coffee!

We both wore uniform shirts on this leg because because we didn’t have a visa for Gabon. Sometimes a uniform helps.

‘LOJ’ felt even more sluggish on take-off with full tanks. We estimated it to be 10% overweight - around 4,000 lbs - so again we handled the aircraft as smoothly as possible while we got the feel of it. The C of G was some way aft, within limits, but giving a definite light feel in pitch. ATC weren’t too bothered about what altitude we flew, so before entering Angolan airspace we experimented a little. At 12,000 feet the aircraft was wallowing slightly and as there was no appreciable wind difference between 10,000 feet and 12,000 feet, we eased back down to ten and set cruise power.

The time in Angolan airspace had given us the greatest cause for concern at the planning stage. The overflight clearance had come through very late but we still wondered if the message had been passed on to ATC. We’d also realised by now that the reason our IFR clearances were being issued so promptly was that there was no coordination between adjacent FIRs, and our initial clearance had been only as far as the boundary. So did Luanda actually know we were coming?

We entered Angolan airspace two and a quarter hours after take-off at position ANVAC on airway R987F. The cloud gradually thickened beneath us until we couldn’t see the surface any more. With a layer above us as well we speculated that even if they did scramble a MiG after us, he’d have a hard time spotting us (wishful thinking probably). There was no reply on VHF until an hour or so out from Luanda. I held my breath as Steve made the call, but all was well as Luanda ATC cleared us through the area at FL100. Still, it was a relief to leave Angola behind and enter Gabon airspace. We’d spend five hours over Angola and only been in communication with ATC for the last two hours.

It was starting to get dark as we descended towards Libreville. The cloud had increased considerably but we got VMC downwind and flew a visual approach to runway 16, landing after a flight time of 9:57. Taxying slowly down the long parallel taxy-way we were surprised to see a Westerner run out and marshall us into a parking position close to a hangar. To cut a long story short, the marshaller turned out to be the local Beechcraft agent who really helped smooth the way for us at Libreville. The refueller arrived straight away, the agent drove us through a hole in the airport fence (uniform shirts not required!), checked us into the airport hotel, then joined us for a drink and promised to send a driver to collect us in the morning. Apart from an extravagantly expensive bottle of wine that Steve insisted I bought with dinner, it had been a very successful day.

Day Three - Libreville to Dakar

An early start this time, with a planned 0530 Zulu take-off and and estimated 12:15 flight time. Again, I checked the weather and filed the flight plan while Steve looked over the aircraft.

We were pleased that we’d refuelled the night before as a steady drizzle was falling. The forecast was good though, with the lower cloud clearing an hour into the flight and no significant weather until the thunderstorms started building later in the day.

Sure enough, we climbed up through the overcast and emerged into the sunshine at 6,000 feet. The airway R979D runs almost directly from Libreville to Abidjan, an overwater leg of 850 nm and up to 250 nm off the coast. The risk level on this leg was obviously high, but we reasoned that we’d be able to get a radio call out to someone if the engine failed, pass an accurate GPS position, and then be able to talk to overflying aircraft from our dinghy on the handheld. We also had a handheld GPS and a handheld emergency locator beacon, so overall we considered it a risk worth taking. The alternative would have been to follow the coast around to Abidjan which would have required overflight clearances from at least Benin, Nigeria and Ghana.

Naturally, the aircraft knew we were on a long overwater leg. A couple of hundred miles out the rpm started fluctuating slightly, maybe plus and minus 50. We were running off the ferry tank at that stage so perhaps the gravity feed wasn’t producing enough pressure or there was some kind of cavitation in the fuel line? Sandro had fitted an electric pump in the fuel line from the ferry tank, so we decided to switch it on to see if it made a difference.

It did. I switched on the electric pump and the rpm dropped straight down to 1500! The engine carried on running but my heart nearly stopped. I banged the pump off, let the engine settle down again, and looked acro!/system/1/user_files/files/000/013/461/13461/80f44a3cc/large/1998_09_03_04_windhoek.jpg!

ss to Steve who was looking at me disapprovingly. What had we been thinking? Why on earth start experimenting with electric fuel pumps two hundred miles off the coast of Central Africa?

The rpm resumed its slight wobble and we decided that was fine. Coasting in over Abidjan, I swear, the needle nailed itself to the 2300 mark and we never saw another fluctuation again. Spooky, or what?

The flight across the Ivory Coast and Guinea was surprisingly hard work. The thunderstorms were developing fast, huge columns of unstable air which we had no desire to see the insides of. We had no comms with Guinea until we almost left their airspace so we zig-zagged our way in a general north-westerly direction avoiding the build-ups visually. Later on in the afternoon, as the temperature dropped, the thunderstorms died away giving us clear and smooth air on the descent into Dakar.

Flight time for day three 12:13, fuel remaining 40 gallons.

Day Four - Dakar to Faro

The bowser driver had already gone home when we’d parked ‘LOJ’ the night before so we weren’t away quite as quickly as other days. We still had plenty of cigarettes to give away so a couple of packets went the driver’s way once the refuelling was complete.

Airborne at 0750 Zulu with a straight out climb to the north towards the Canary Islands, today’s flying would be almost entirely over water, but somehow it didn't seem as intimidating as the leg across the Gulf of Guinea. In fact, it turned out to be the easiest day’s flying of the trip. The weather was clear the whole way, and although we picked up a slight headwind to start with which put us 13 minutes late over Tenerife , it later changed to a tailwind and we landed in Faro only two minutes later than planned, at 7 pm local. Flight time for day four was 10:11.

Faro is “light aircraft friendly" and has a highly efficient Flight Planning Office. They accepted our next days’ flight plan and promised us a full briefing pack in the morning. The final consideration before finding accommodation for the night was refuelling. The Air BP card came good again but we made sure the ferry tank was only half full. It was going to be removed on arrival in the UK so there was no point in landing there with fuel still in that tank.

Steve tried to talk me into spending the next day on the beach so I had to buy him another expensive bottle of wine. What the heck, we were nearly home!

Day Five - Faro to Peterborough Sibson

The planning didn’t work out too well on the last day. My family was expecting us to arrive at Peterborough Sibson (EGSP) at 4:30 local and I was determined to land as close to that time as possible.

The estimated flight time was 7:36 so a take-off at 0755 Zulu would be spot-on. Just to be safe, we took off 5 minutes early, figuring it would be easier to lose the time than make it up. Northbound over Portugal the headwind component got stronger and stronger and we slipped from 5 minutes up to 15 minutes down. “Don't worry," said Steve, “It’ll change to a tailwind as soon as we set out across the Bay of Biscay". “Yes, but what if it doesn’t?" I replied, easing the rpm up to 2500. As usual, he was right and I was wrong. By the time we crossed the French coast and turned at Nantes we were 15 minutes ahead of schedule, despite reducing the rpm back to 2200 and, for the first time ever, reducing the manifold pressure in the cruise back to 22 inches. After turning at Jersey we were talking to London, probably the first time they’d heard a ‘ZS’ callsign from a light aircraft. We cancelled IFR over Compton VOR and let down for a quick flypast at Denham (EGLD) before turning north again, now at 2,000 feet, for the last 20 minutes up to Sibson. We got there at 4:20 local, and after five days’ flying, it seemed ridiculous to fly around in circles just to land at half past, so I gave up gracefully and we landed just as the family car drove onto the airfield. We didn’t drink red wine that night, we drank champagne!

Lessons Learned

Planning, planning, planning. Talk to everyone you can think of before embarking on a long ferry flight in a single. Instructors, ferry pilots, commercial pilots, charter pilots. Pick their brains, ask about routes, weather, admin problems, accept their good ideas and reject their bad ones. Start collecting overflight and landing clearances as early as possible - it always takes longer than you'd think. Get a fuel card or two. Fly IFR if possible. Take lots of safety equipment and don’t forget spare batteries for the gadgets. Safety equipment is insurance that you probably won’t need, but there again... Don’t trust a Psion for dawn and dusk calculations, and finally, don’t fiddle with fuel pumps two hundred miles out to sea!

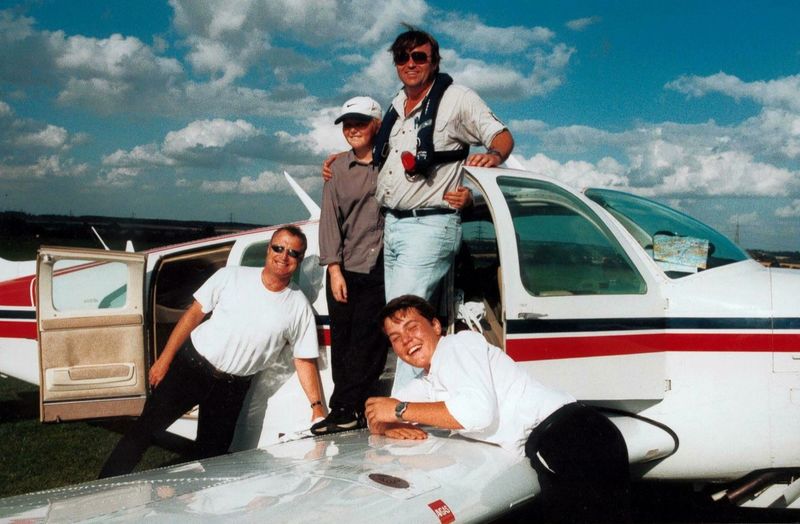

A few weeks' later, on the UK register:

May 25th, 2016